I wrote an article earlier titled "Were Chinese Characters Created by Right-Handers?" which discussed the reasons behind right-handed individuals creating Chinese characters. Today, I'd like to discuss another well-known but seldom explored topic: why did ancient people write from top to bottom? Some may ask, "What about writing from right to left?" Today, I'll address this question.

Before delving into this, I'd like to touch on Shell Bone Script.

The earliest form of Chinese characters was Shell Bone Script, which dates back over 3500 years. There's a common misconception that ancient people wrote characters on Shell bones, which is why we refer to it as Shell Bone Script. However, this is not entirely accurate. During the Shell Bone Script period, people primarily wrote characters on bamboo slips, not on Shell bones. Only during divination ceremonies were characters inscribed on Shell bones, which were then placed in a fire and cracked to predict fortunes.

Divination was conducted for predicting major events and was very rare. Moreover, the turtle shells and cattle bones used for divination were carefully selected and meticulously processed, making them scarce materials affordable only to emperors or tribal leaders.

So, why do we call it Shell Bone Script? The earliest Shell Bone Script bamboo slips, over 3500 years old, have already decayed and didn't survive. However, Shell bones, which can endure over 3500 years without decay, were discovered, so what we find are inscriptions on Shell bones. Originally, it was not called Shell Bone Script, but rather "Yinxu Script" because it was mostly discovered in the Yinxu site in Henan. However, it was later found in other places, and in great quantity. It became evident that "Yinxu Script" was not accurate, so it was changed to "Shell Bone Script."

Ancient bamboo slips were generally 6-8 millimeters in width, roughly the width of a small finger, and up to 45 centimeters long. Writing on such bamboo slips greatly restricted horizontal writing. Therefore, many Shell Bone Script characters are vertical, as horizontal writing was impractical, but vertical writing allowed for extension.

The Shell Bone Script characters above (from left to right): Dog, Pig, Tiger, Horse, Elephant, Bed.

All of them are written vertically. Thus, writing from top to bottom on bamboo slips became the only viable option.

In the Shell Bone Script era, due to the constraints of bamboo slips, it was impossible to write horizontally, whether from left to right or from right to left.

Ancient people did not write just one bamboo slip at a time, but rather many. Since one bamboo slip could only accommodate a few characters, writing an article required dozens or even hundreds of slips. If it was a book, it could be over a thousand slips, or even more, bundled together. If someone had read more than a dozen books, they would have to use a cart to carry them.

So, how did ancient people write on bamboo slips? As I demonstrated in my earlier article, ancient people wrote with their right hands. Therefore, the right hand would hold the brush while the left hand held or supported the bamboo slip. After finishing writing on one bamboo slip from top to bottom, the left hand would move it away, and then a blank bamboo slip would be picked up to continue writing. This process would be repeated until finished. Afterwards, the written bamboo slips were strung together with fine strings, rolled up into a bundle, and became an article or a book.

Now, there's a question: Were the blank bamboo slips placed to the left or the right of the writer? And where were the completed slips placed?

If the blank bamboo slips were placed on the left, then the left hand would conveniently pick them up, and after writing, push them to the right (they couldn't be placed back on the left, as they would mix with the completed slips).

If the blank bamboo slips were placed on the right, the left hand would need to reach over the right hand holding the brush or reach underneath it to get a blank bamboo slip. This would be an awkward and difficult motion. Of course, the right hand could move closer to the body or be lifted higher to make way for the left hand. However, it would be inconvenient with a brush in the right hand dipped in ink.

You might say, placing the blank bamboo slips on the left also has the problem of where to put the completed slips, isn't that also awkward? However, after a completed slip is pushed to the right, it only needs to be pushed towards the right. But the hand picking up the blank slips must accurately pick out one from the stack of blank slips and hold it. It's very easy to take a blank bamboo slip if they are on the left. This is much easier than placing the blank bamboo slips on the right and reaching over with the left hand from the right side to get a blank slip. It can be imagined that the ancients placed the blank bamboo slips on the left and pushed the completed slips to the right.

In this case, the second completed bamboo slip would be pushed to the left of the first completed bamboo slip, the third to the left of the second, and so on. Ultimately, the completed slips would be arranged with the first completed slip on the far right and the last completed slip on the far left. They would then be strung together with string. When reading, one would start with the first slip on the far right and read from top to bottom. Once at the bottom, the eyes would move up and continue reading the second slip on the left. This process would repeat until finishing the last slip on the far left.

To summarize, traditional Chinese writing only involved writing from top to bottom and did not include horizontal writing from right to left.

Now, let's discuss the impact of the invention of paper on the structure and writing of Chinese characters.

It is commonly acknowledged that Cai Lun of the Eastern Han Dynasty invented papermaking. However, many signs suggest that papermaking workshops existed among the common people before Cai Lun. Cai Lun, commissioned by the court, collected and refined the folk papermaking techniques, making significant improvements and creating large-scale papermaking. This industrialized papermaking and turned paper into an affordable commodity for ordinary people. Since then, paper replaced bamboo slips, greatly enhancing social communication, productivity, and the evolution of Chinese characters themselves.

As mentioned earlier, bamboo slips severely limited horizontal writing. However, with the advent of paper, writing transformed from one-dimensional vertical to two-dimensional. "The sky's the limit" – people finally got the opportunity to spread out horizontally. Initially, people straightened out the inward-curving lines of Seal Script, creating horizontal strokes known as "Heng" or "Na." The slender Seal Script became the short and wide Clerical Script.

From top to bottom: wood, dragon, water, enter.

The images above show the impact of paper on the structure of Chinese characters: Long and narrow characters (Shell Bone Script, Seal Script, Large Seal Script, Small Seal Script) evolved into short and wide characters (Clerical Script). The inward curves of Seal Script became outward straight lines in Clerical Script. This change was a form of rebellion after enduring long-term suppression of horizontal writing in Chinese characters.

Liqi Stele – Han Dynasty

Following Clerical Script, the structure of Chinese characters did not change. Regular Script and Song Typeface maintain the same structure as Clerical Script; only the brush strokes' pressure and lifting differ. However, Regular Script and Song Typeface's horizontal expansion is not as pronounced as Clerical Script, appearing more balanced in both vertical and horizontal aspects. This was a return to balance after the emotional release following the suppression.

Now, let's look at the influence of the advent of paper on the way Chinese characters are written.

As mentioned earlier, during the Shell Bone Script era, people were accustomed to writing from top to bottom and then moving left one line, continuing from top to bottom. This eventually led to a format similar to bamboo slips. This was a result of habitual inertia, not necessarily a more natural way of writing.

Jiucheng Palace – Tang Dynasty

The emergence of paper gave rise to running and cursive scripts, as it allowed for more expressive and free-flowing strokes to convey the emotions of the writer.

Lantingxu – Sui Dynasty

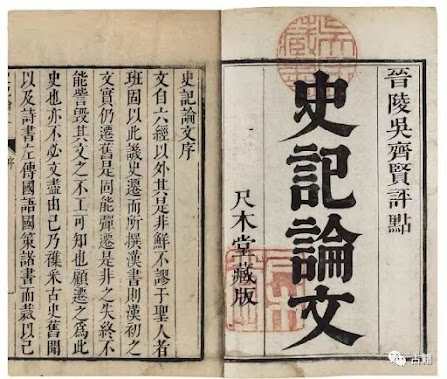

Regardless of the font style, writing always goes from top to bottom, with vertical columns arranged from right to left. This is also the format used in traditional thread-bound printed books.

Shiji (史記), or Historical Records

After the advent of paper, the habit persisted, and people began writing from the upper-right corner, moving from top to bottom. Then, they would shift one line to the left and continue from top to bottom. This final format was consistent with the previous method of writing on bamboo slips. This was a matter of upholding the same format as bamboo slips out of habit.

In conclusion, traditional Chinese calligraphy has never involved writing horizontally from right to left. There are very few instances where Song Typeface characters are printed in a horizontal format from right to left. This is due to a lack of understanding of traditional Chinese character writing on the part of publishers, rather than an authentic historical practice. Ancient people did not write in this manner.

Conclusion: In the history of Chinese calligraphy, there has never been a practice of writing horizontally from right to left. The few instances of Song Typeface characters being printed horizontally from right to left are a result of publishers' ignorance of traditional Chinese character writing. Ancient people did not write this way.

Note: Update information

1, Amazing Chinese Characters blog has changed name to Learn Chinese with Pictography, and changed its URL address too, the new URL is

Learn Chinese with Pictography.blogspot.com/

2, Pictographic Chinese Calligraphy blog has changed name to Chinese Pictographic Calligraphy, and the new URL is

Chinese Pictographic Calligraphy.blogspot.com/

You are welcome to access the new sites for Chinese learning. Please update your bookmarks.